The Transmutation in Place

It was as seemingly ‘simple’ as the placement of one’s feet on the bare rock and feeling the solidity in the body and mind, and like the rocks, what had arrived to this continent culturally outside of the Beingness is silenced, far away, America’s definition from lesser minds remote. A different strength, a different kind of freedom, a different wildness of spirit (not reactive, but of its self–and that leads true revolutions) is known, a different, more true voice. And then there is the fire of inspiration from there, not exploitative in the least, but Place revealing itself in state of pure Being, its attributes of Place evident and speaking. Importantly, others from this Place had lived here hundreds of years before and left their own tell-tale remnants of what they expressed and what mattered most to express in their existences in form, in this landscape of form, form and transcendence.

Another aspect of this is what will open when one steps into that Being reality where one can examine inside the stillness, and thus outside which automatically turns into a different Place. Willa articulated this transition in her 1915 The Song of the Lark from her experience there at Walnut Canyon outside of Flagstaff. She had arrived to her own space and expression from this core of Being and could now examine the flow of culture and that it most certainly could be changed from which it came–what had arrived to America and how it had gone thus far feeding from appetite (a sign of merely mortal form, as forewarned by the ancients) (appetite for money, fame, attention, etc. is the tell-tale of inner empty shell as it seeks outside of its ghost self).

The line of art came from France and Italy, its ‘religion’ and legends expressed there to its fullest divine beauty from Florence and Rome to Paris and Marseilles. But importantly here in the American Southwest was also the freedom of the absence of what had been built up around the guarding of it in Rome into structure (the obtrusive walls even Dante experienced) and the not-yet-fully transmuted transmission of the inheritance of Jerusalem that had been strangled there by war and politics and thus had artistically, spiritually, and physically in relics migrated to the draw of life, for the inspiration of life, to the very sensuous arms of the Bouches-du-Rhône where She, the Magdalene, desired most to live.

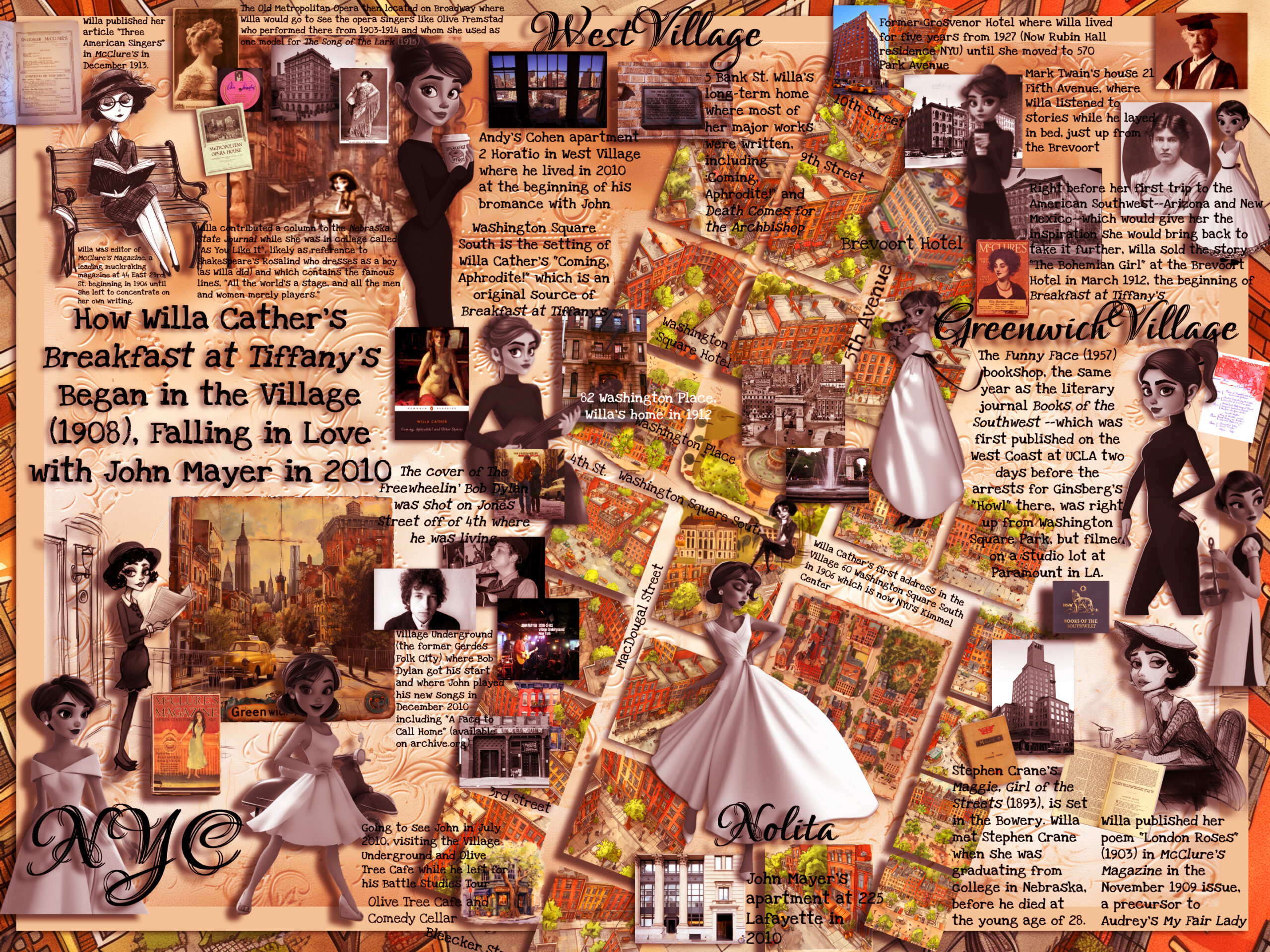

Willa Cather’s “The Bohemian Girl” is the original beginning of Breakfast at Tiffany’s. Audrey Hepburn returned this originality to its more profound, alive path of eternal voice and Being through her own humor, staying true to herself, and the defiant courage of resistance, wildly courageous acts she didn’t have to give herself to but with extraordinary beauty, love, and kindness lifted them to forever expression.

In 1850 my great-great-great grandfather, a jeweler, brought his family from Bohemia to Cincinnati, Ohio (where I was born), coming to the same city and year as the ordination of the first Archbishop of Santa Fe and the vast expanse of the American Southwest, the first of the five of this line of Archbishops from France.

Willa Cather’s “Coming, Aphrodite!” set on Washington Square Park is the original setting and characters of Breakfast at Tiffany’s. Not knowing any of this, two years after my own miraculous first trip to Santa Fe in 2008, I would come to fall in love with John Mayer in the very same neighborhood of Greenwich Village. Audrey Hepburn had started putting it back in 1957 in Funny Face in the bookshop set there in the story based on her friend, photographer Richard Avedon.